From Breadbaskets to Battlegrounds: India’s Polarised Prospect

Lulu Farshana M

Dr. Namrata

In India, the growing disparity

between rich and the poor is considerably more visible than it was during

British colonial rule. Economic inequality is marked by gaps in income, wealth

distribution, and access to resources, which fuels resentment and discontent

among various socioeconomic groups. This sense of discontent frequently

manifests as political polarisation, in which opposing factions align with

conflicting ideas and parties ends up in increasing societal differences. Inequality

and polarisation have historical connections to the potential for social

conflict. A highly unequal or polarized society may be more prone to conflicts,

highlighting the social implications of economic disparities. Politicians use

these disparities for electoral support, resulting in policies and rhetoric

that exacerbate economic inequities. In India, economic inequality and

political polarisation are deeply intertwined, exerting significant influence

on the nation's socio-political landscape. Thus, addressing economic inequality

is crucial for mitigating political polarisation and fostering a more inclusive

and stable democratic environment in India.

Key words: economic disparity,

income inequality, political polarisation, social conflict

Background

India, the world's largest democracy, has long been a nation of contrasts (Guha, 2017). From its bustling metropolises to its remote rural villages, the disparities in wealth and opportunity are striking. Over the past few decades, economic disparity in India has grown (Sharma & Vidyapith 2023), creating fertile ground for political polarisation (Thampi & Anand 2017). The vast and growing gap of political attitudes and identities among the public that undermine the pursuit of a common good (Levin et al., 2021). The upsurge is often compounded by the rise of ideologically divided masses and radical political parties. In recent decades, political polarisation has intensified globally and has been a disruptive force in societies across the world, from advanced countries including the US and those in Europe to the developing world such as India, Korea and Turkey etc (Moraes & Béjar 2023; Bou-Hamad & Yehya 2020). Understanding the connection between economic inequality and political polarisation is essential to address the root causes of this phenomenon and to seek sustainable solutions (Suhay, 2022; Church, 2020). The issue of political polarisation linked to economic disparities in India is critical due to its potential to undermine the nation’s democratic fabric and socio-economic stability (Schneider & Shevchuk, 2020).

India, beyond the

emerging economy also faces unique challenges where economic inequalities and

social stratifications can significantly influence political dynamics. To

examine the driving forces behind political polarisation, the current

well-developed scholarship has mainly examined factors such as the changes in

socio-demographic cleavages. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these

disparities (Zhao et al., 2023), disproportionately affecting the poorer

sections of society, leading to heightened frustration and alienation (Raphael &

Schneider, 2023). This economic distress has translated into deeper political

divides, as marginalized groups feel increasingly neglected by mainstream

political entities (Nandwani, 2023; Varghese,

2023). This situation calls for urgent and effective policy

interventions to address economic inequalities and foster inclusive

development, which are crucial for maintaining the stability and integrity of

India’s democracy.

Since the 1990s, there

has been a rise in both bipolarization and multidimensional polarisation, which

has widened inequality in tandem with rapid economic growth (Motiram &

Sarma, 2014). The liberalisation policies brought about considerable changes to

the Indian economy (Jayadev et al., 2007). Rapid economic growth was sparked by

these reforms, lifting millions out of poverty and fostering the emergence of a

growing middle class.

Economic disparities

and political polarisation have markedly intensified since the landslide

electoral victories in 2014 (Sahoo, 2020). The era has witnessed significant

economic growth, yet the benefits have disproportionately favoured the wealthy,

exacerbating income and wealth inequality. The advantages of this expansion,

nevertheless, have not been felt equally by everybody. The wealthiest 1% of

Indians own more than four times as much as the poorest 70% of the population (Himanshu,

2022). The World Inequality Report (2022) states that only 13% of the nation's

income is held by the poorest 50% of the population, while the top 10% owns 57%

of it. The fact that 53% of India's wealth is owned by the richest 1% of the

population, especially after the pandemic, serves as more evidence of this

widening wealth disparity. India currently has more billionaires per capita

than any other country in the world, with a sharp rise in income disparity that

has surpassed that of the United States, Brazil, and South Africa (Bharti et

al., 2024). The widening divide in India between the rich and the poor is even

more noticeable than it was during British colonial control (World Inequality

lab, 2024). Social and political divisions are exacerbated by such glaring

economic inequality between various economic classes, which is a major factor

contributing to political polarisation.

These results in

tensions between different social groups, central and state governments, and

supporters and dissenters of the ruling party. The permanence of coalition

politics in India can partly be explained by these economic disparities and

political polarisations. The deterioration of economic conditions is impacted

by political engagement in a way that goes beyond conventional institutional

bounds to include economic goals and concerns about inequality. It has been

typically examined from an economic perspective. However, it becomes more and

more politicized in recent decades, causing a wide range of detrimental

political consequences. Moreover, income inequality can lead to political

inequality by affecting preferences for redistribution, political

participation, and policy responsiveness, ultimately undermining democracy (Polacko,

2022). Growing inequality could undermine social mobility, induce violent conflicts,

and generate political tensions (Justino, 2004). At the same time, there is

widespread concern that the “vicious cycle of poverty” and rising income

inequality constitute an important cause of political polarisation that

threatens to divide and even destabilize a nation (Sen, 2018; Guha-Khasnobis &

Agarwal 2014; Sen & Himanshu 2004).

Moreover, the enduring

disparities in electoral participation between different socioeconomic groups

are partly explained by the mediating role of health, where poor health

resulting from socio-economic disadvantage demobilizes eligible voters,

limiting the political voice of the disadvantaged (Nelson, 2023). This

interplay between economic conditions, inequalities, and political engagement

underscores the complex relationship between economic disparities and political

participation in India. The privatization and globalization policies have

primarily benefited those with higher education, often accessible to the

already privileged sections of society, leaving the middle and lower classes

with dwindling opportunities for upward mobility. By fostering majoritarian

politics, intensified communal and ideological divisions. The rise in

majoritarian rhetoric and policies has often marginalized minority communities,

further polarising the political landscape.

Economic inequality causes individuals who feel left behind to become disillusioned, which in turn exacerbates political polarisation in a number of ways. Marginalised groups frequently feel abandoned by the political system because they experience long-term unemployment, inadequate healthcare, and inadequate education (Varghese, 2023). Voter dissatisfaction may take the form of apathy or, on the other hand, support for populist leaders who offer drastic reforms. People who are afraid about their financial situation frequently turn to their identity groups whether they are regional, religious, or caste-based for comfort (Bauernschuster et al., 2009). Political parties use these identities as a means of building voter bases, which exacerbates division (Huber & Suryanarayan, 2016). Economically disadvantaged groups, for example, might unite behind leaders who swear to defend their interests, while wealthier segments might back those who promise to uphold the status quo. Growth in the economy has been disproportionately concentrated in cities, widening the gap between them and rural areas (Anand & Thampi, 2016). Rural residents feel more and more isolated since they frequently lack access to basic infrastructure and employment possibilities. Political polarisation is largely a result of the urban-rural divide, as evidenced by the different political priorities and preferences of urban and rural voters.

Theoretical background

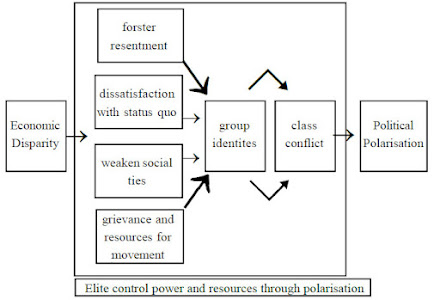

A comprehensive overview of various theoretical frameworks that

elucidate the relationship between economic disparity and political

polarization (Table 1). Political polarization, the increasing ideological

distance and hostility between different political groups, has been a growing

concern globally. Understanding the theoretical underpinnings can help in dissecting

how economic inequality influences political behaviour and societal divisions

(Figure 1).

|

Theoretical

Framework |

Key

Proponents |

Core

Concepts |

Relationship

between Economic Disparity and Political Polarization |

|

Relative

Deprivation Theory |

Ted

Robert Gurr |

Focuses

on the perception of inequality and deprivation relative to others. |

Economic

disparity leads to feelings of relative deprivation, which can foster

resentment and political polarization. |

|

Economic

Voting Theory |

Anthony

Downs, Douglas Hibbs |

Economic

self-interest and economic performance are the main factors that influence

voters' political decisions.. |

Increased

economic inequality can cause discontent with the current state of affairs,

which fuels polarisation as various groups push for reform. |

|

Social

Identity Theory |

Henri

Tajfel, John Turner |

Belonging

to a group gives people a sense of identity and self-worth.. |

Economic

inequality can intensify group identities (such as class and ethnicity),

increasing polarisation and the differences between in-groups and out-groups. |

|

Class

Conflict Theory |

Karl

Marx, Friedrich Engels |

There

are competing classes in society, especially between the bourgeoisie and the

proletariat. |

Class

conflict is exacerbated by economic inequality, which fuels political

polarisation between the status quo's supporters and detractors. |

|

Modernization

Theory |

Seymour

Martin Lipset |

Social

structures and political institutions change as a result of economic

development and modernisation.. |

Development

might theoretically lessen polarisation by reducing economic gaps, but quick

changes can sometimes momentarily make polarisation worse. |

|

Elite

Theory |

C.

Wright Mills, Gaetano Mosca |

There

is a constrained ruling elite and the general populace in society. |

The

elite, who frequently profit from economic inequality, may utilise political

division as a tactic to hold onto power and control over resources. |

|

Social

Fragmentation Theory |

Robert

Putnam, Francis Fukuyama |

Social

dispersion brought on by economic inequality can erode trust and social

cohesiveness. |

As

various groups pursue their interests, growing economic disparity can cause

social bonds to deteriorate and political polarisation to increase. |

|

Rational

Choice Theory |

Gary

Becker, James Buchanan |

People

make decisions based on reasoned calculations in order to maximise their

gains.. |

Because

groups may make different logical decisions as a result of economic

inequality, political polarisation may result when they support policies that

serve their interests.. |

|

Resource

Mobilization Theory |

John

McCarthy, Mayer Zald |

Resources

become available and are mobilised to form social movements. |

Economic

inequality can fuel political movements by providing the complaints and

resources they need to get organised, which can polarise society.. |

Conceptual understanding from the theories

The analysis conducted

by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute underscores the growing

political polarisation in India, which has been further aggravated by the

amplification of economic inequities subsequent to the COVID-19 outbreak (Figure

2). V-Dem's reports indicate that India's political division has gotten more

extreme recently. The COVID-19 epidemic has exacerbated already-existing

economic disparities, which have contributed to this polarisation. Lower-income

groups have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic's economic

effects, which have also widened already-existing economic gaps. The economic

recession brought on by the pandemic resulted in a large number of job losses

and income reductions, especially for the most disadvantaged groups. The

public's discontent and mistrust of governmental institutions have been

exacerbated by this economic strain, further polarising the political

landscape. Disinformation and inflammatory rhetoric from political leaders

exacerbate the heightened partisan differences and social tensions that reflect

the rising polarisation. The results also indicate that these economic and

social differences pose serious threats to democracies like India. However,

when it comes to resolving these concerns, democratic institutions typically

outperform authoritarian regimes since they tend to guarantee greater public

health, economic growth, security, and the supply of public goods. Overall,

there is cause for concern regarding the relationship between political polarisation

and economic inequality in India, particularly in light of the recent pandemic.

Figure 2. Graph of

political polarisation (V-Dem, 2024)

Political polarisation

and income inequality in India reveals several significant insights and raises

important questions about the socio-political dynamics at play. The data shows

a clear trend where rising income inequality, as measured by the Gini

coefficient, is associated with increasing political polarisation (Figure 3).

Initially, from 2000 to 2013, political polarisation remained relatively low

and stable despite the steady rise in inequality. This period of political

stability might be attributed to various factors such as economic growth,

social policies, or a lack of significant political upheavals. Political

polarisation has sharply increased since 2013, albeit this could be attributed

to a combination of factors such as the long-term effects of inequality,

growing dissatisfaction across various socioeconomic groups, and possibly the

rise of more divisive political rhetoric and policies. Even while the Gini

coefficient has continued to climb, the variations in political polarisation

that have been seen since 2016 indicate that other factors may possibly be

influencing political dynamics. These could include significant political

developments, governmental transitions, choices made on public policy, or even

external factors like geopolitical tensions or economic crises. Though this

does not immediately translate into less polarisation, it may point to a

plateau in income inequality or to effective measures taken to address extreme

disparities. This illustrates the complex and gradual influence of economic

policies on political sentiments. the unmistakable factual link that has been

shown over a significant amount of time between growing political polarisation

and wealth disparity in India. In addition to emphasising patterns, this

research also shows the potential lag effect of economic disparities on political

dynamics, providing a unique longitudinal viewpoint. This analysis offers a

thorough overview extending over two decades, in contrast to many other studies

that concentrate only on short-term data or isolated instances. This insight into

how long-term economic patterns impact political landscapes.

Figure 3. Combined

graph of Political polarisation and Gini coefficient

New theories regarding

the connection between political behaviour and economic inequality may arise as

a result of the interconnectedness. One such argument, for example, is that

long-term economic inequality feeds the public's sense of disenfranchisement

and division, which feeds political polarisation. A different hypothesis would

investigate how policy choices and political discourse might either lessen or

exacerbate the impact of inequality on political divide. Moreover, the results

indicate that mitigating income inequality via equitable economic policies and

social justice campaigns may be crucial in diminishing political division and

thus fostering a more unified and steady community.

Future research and the development of policies targeted at tackling political and economic issues in concert may build on this integrated approach. Future projections show that unless substantial efforts are taken to address the underlying causes of inequality, political polarisation may either stay high or even worsen if income disparity keeps rising. Polarisation may be lessened by policies that support social fairness, equitable resource allocation, and inclusive economic growth. Political stability also depends on encouraging political discourse and minimising divisive speech. It would be essential to comprehend and deal with the interaction of political and economic elements in order to guarantee a more cohesive and stable socio-political climate in India. Between the years 2000 and 2022. Political polarisation and the Gini coefficient show an increasing trend over this time. Up until about 2005, political polarisation was comparatively constant. Then, it started to climb dramatically, peaked around 2015, then slightly declined before rising once more by 2022. Simultaneously, the Gini coefficient exhibits a consistent upward trend, signifying a growth in income disparity. The concurrent increase in both measures raises the possibility of a link and shows that the widening political gulf may be exacerbated by rising income disparity. This association highlights how crucial it is to solve economic inequality in order to perhaps lessen political division.

Notable Cases and Key

Incidents

A

detailed chronological examination of significant incidents and policy

developments in India (Table 2) reveals the complex connection between economic

inequality and political polarisation. Covers the early 1990s to the present, highlights

notable events that have had a substantial impact on the country's economic and

political environments. The narrative begins with 1991's historic economic

liberalisation, which heralded a new age of rapid economic growth, increasing

foreign direct investment (FDI), and job creation. This time marked the

creation of a wealthy elite and intensified the urban-rural split, setting the

framework for future socioeconomic inequities. The Babri Masjid demolition in

1992 stands as a critical juncture, religious polarisation is rising and

impacting the political discourse, with long-term consequences for community

ties and political alignment (Chandhoke

& Priyadarshi, 2009).

As India transitioned

into the 2000s, the IT and service industry boom highlighted the country's

economic dynamism, resulting in significant wealth creation in metropolitan

areas. However, this growth revealed differences between geographies and social

groupings. Concurrently, substantial governmental interventions, such as the

National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) and the implementation of

reservations for Other Backward Classes (OBCs), attempted to redress some of these

discrepancies. Despite these efforts, events such as the Gujarat riots and the

anti-corruption campaign highlight the persistent conflict between economic

advancement and social fairness (Jaffrelot, 2015). Following

2014, a new government emerged with promises of economic reforms, most notably

the "Make in India" initiative and the controversial demonetisation

policy of 2016. These measures, while intended to stimulate economic growth,

generated political polarisation and arguments about their efficacy and goal (Mahmood, 2017).

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) implementation serves as an example of the

challenges associated with striking a balance between economic changes and

regional disparities. However, its effect on economic inequality has come under

fire because, notwithstanding exemptions for necessities, the regressive nature

of the tax system unfairly impacts lower-income people (Mukherjee, 2020). This

discrepancy deepens ideological rifts, escalating political polarisation and

marginalised groups' sense of economic unfairness. Regional inequities have

been exacerbated by the GST's implementation issues, such as the costs placed

on small enterprises to comply with the law. This has led to heated discussions

between political ideologies that support decentralised versus centralised

fiscal policies. As a result, the GST has not only changed the economic

landscape of India but also the socio-political landscape, intensifying

ideological and economic divisions.

Recent

years have seen substantial social movements and legal advancements that

intersect with economic and political challenges. Farmers' rallies against

controversial agriculture policies, as well as Dalit protests (Bharat Bandh),

underscore the continuous battle for economic equity and social justice. The

repeal of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir, as well as the impact of the

COVID-19 pandemic, highlight the complexities of governmental decisions and

their broader socioeconomic consequences. Recent developments from 2022 and

2023, including ethnic unrest in Manipur and the Supreme Court's decision on

the SC/ST Atrocities Act. These events demonstrate the ongoing impact of

economic and social inequities on political polarisation, illustrating both

their permanence and change in modern India. Caste plays a significant role in

economic inequality, with lower caste groups such as Dalits facing structural

disadvantages. This issue has been highlighted by movements such as the Bhim

Army's action in Uttar Pradesh and the Dalit marches in Maharashtra in 2018

against caste-based violence and prejudice. Political polarisation arises as a result of caste-based economic

imbalances, when marginalised groups mobilise against legislation and political

parties they believe will perpetuate their economic and social enslavement. The

rise of Dalit political movements, as well as their support for social justice

and economic redistribution parties, demonstrate how caste-based economic

inequities aggravate political polarisation (Weiner, 2001;

Jaffrelot, 2015).

Farmer Protests and the Agrarian Crisis (2020–2021) Protests erupted across the country in 2020 in response to three agriculture bills passed by the Indian government that were perceived to promote large corporations over local farms. For more than a year, farmers, largely from Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh, occupied Delhi's borders and demanded that the rules be lifted. This episode highlights how long-standing issues such as low crop prices, debt, and insufficient support may cause economic hardship for farmers (Kumar, 2021; 2024). The protests' widespread support from opposition parties has created a visible political schism between the incumbent government and its opponents. The agricultural crisis exposed the link between political division and economic grievances. This overview gives a nuanced viewpoint on how economic policies, social disparities, and political polarisation overlap and grow over time.

Table 2. Key incidents and policy developments connect economic

inequality and polarisation in India.

|

Year |

Event/Case |

Economic

Impact |

Political

Impact |

|

1991 |

Economic

Liberalization Begins |

Rapid economic

growth, increasing FDI and employment creation. |

The rise of an

affluent elite has deepened the urban-rural gap. |

|

1992 |

Babri Masjid

Demolition and Subsequent Riots |

Economic

disruption due to the communal conflicts. |

Increased

religious polarisation, emergence of Hindutva politics. |

|

2000-2010 |

IT and Service

Sector Boom |

Creating new

wealth in urban areas and IT hubs. |

Political

power transfers towards metropolitan regions; the middle class emerges as a

crucial voter base. |

|

2002 |

Gujarat Riots |

Economic

losses in impacted towns, and long-term distrust affecting local economies |

Political

consolidation of Gujarat Governmet, polarisation along religious lines |

|

2005 |

NREGA

(National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) |

Ensured

economic security for rural populations |

Political

mobilization of rural poor |

|

2006 |

OBC

Reservations in Educational Institutions |

Increased

access to education for backward classes |

Political

polarisation over reservation policy has a tremendous impact on student

politics. |

|

2014 |

General Election |

Promises of

economic reforms, "Make in India" initiative |

Strong

mandate, polarisation based on economic promises, and development of Hindutva

politics. |

|

2016 |

Demonetization |

Disruptions in

the informal sector, cash shortages |

Political

polarisation, dispute on economic efficacy, and intention. |

|

2017 |

Implementation

of GST (Goods and Services Tax) |

Simplification

of tax structure, compliance costs |

Mixed

reactions, economic differences among states, and political disagreement |

|

2018-2019 |

Farmer

Protests |

Highlighted

agrarian distress |

Political

mobilization of farmers, impact on 2019 elections |

|

2018 |

Dalit Protests

(Bharat Bandh) |

Highlighted

economic and social issues faced by Dalits |

Political

mobilisation of Dalit communities, challenging government. |

|

2019 |

Abrogation of

Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir |

Economic

uncertainty in Jammu and Kashmir, impact on tourism and businesses |

Political

polarisation, heightened tension in Jammu and Kashmir, national debate on

autonomy and security |

|

2020 |

COVID-19

Pandemic |

Economic

contraction, job losses, migrant crisis |

Political

debates about crisis management and polarisation over lockdown tactics. |

|

2020-2021 |

Farmers'

Protest against Farm Bills |

Perceived

threat to small farmers' incomes |

Large-scale

demonstrations, political coalitions, and polarisation over agricultural

reforms |

|

2020 |

Delhi Riots |

Economic

losses in affected areas, impact on local businesses |

Increased

communal tensions, political discussions on law and order, and religious

polarisation |

|

2022 |

Anti-Muslim

Riots in Karnataka |

Economic

impact on affected communities and disruption in local businesses |

Increased

communal polarisation, political disagreements regarding state and national

government responses |

|

2022 |

Release of the

film "The Kashmir Files" |

Increased

interest in Kashmir-related tourism, disagreement over the film's

representation of historical events. |

Political and

communal polarisation, impact on the discourse about Kashmir |

|

2023 |

Manipur Ethnic

Violence |

Severe

economic upheaval, population displacement, and effects on local economies |

Increased

ethnic and political polarisation, leading to examination of state and

federal government actions. |

|

2023 |

Supreme Court

Verdict on SC/ST Atrocities Act |

Potential

effects on social and economic protections for marginalised communities |

Political

reactions surrounding the preservation of Dalit and tribal populations, and

their impact on upcoming elections |

Conclusion

The

central thesis posited that growing economic disparities significantly

contribute to the intensifying political divide, with marginalized groups

seeking greater representation and wealthy strata consolidating their

influence. The analysis revealed that regions with higher levels of economic

inequality tend to exhibit more pronounced political polarisation, driven by

socio-economic grievances and competing interests. This phenomenon is primarily

driven by the disenfranchised segments of the population rallying behind

populist leaders who promise economic reforms and social justice, while the

affluent segments support policies that favour economic liberalization and

growth, leading to a polarised political landscape.

The

broader implications of these insight are profound for Indian society and

politics. The growing divide poses a significant challenge to India's

democratic fabric, as it undermines social cohesion and effective governance.

Political polarisation fuelled by economic inequality can lead to policy

gridlock, where crucial reforms are stalled due to partisan conflicts. This not

only hampers economic development but also exacerbates social tensions, making

it difficult to address pressing issues such as poverty, healthcare, and

education. To mitigate these effects, it is imperative for policymakers to

implement measures that promote economic inclusivity and equitable growth.

Strategies such as progressive taxation, which can help to reduce income inequality, are essential.

Additionally, substantial investments in education and healthcare can empower

the economically disadvantaged, providing them with better opportunities and

reducing the socio-economic divide. Strengthening social safety nets, such as

unemployment benefits and food security programs, can also play a crucial role

in alleviating economic distress and fostering social stability.

Furthermore, bridging the gap between wealthy and marginalised places can be achieved by tackling regional economic imbalances through focused development projects. To promote more equitable and inclusive economic growth, undeveloped regions can benefit from the establishment of special economic zones (SEZs), which can boost local economies, provide employment, and lessen the burden of migration on urban centres. Future studies should examine how the media contributes to political polarisation, considering its enormous impact on voter sentiment and election results. Further understanding of the causal links between political behaviour and economic inequality may come by examining the effects of regional economic policy on local political dynamics. Longitudinal studies examining the long-term effects of economic policies on political polarisation would be particularly valuable in understanding these dynamics over time. In sum, addressing economic inequality is not only crucial for economic justice but also for ensuring a more harmonious and less polarized political landscape in India. This emphasises how crucial it is to launch coordinated policy initiatives to close the economic gap in order to promote social cohesiveness and democratic stability. Addressing these discrepancies through well-informed policy interventions would be crucial to securing a more egalitarian and politically peaceful future as India grows and changes. Economic inclusion will open the door to a more robust and resilient democracy that can meet the needs and ambitions of all of its people.

References

Appendix

|

Year |

Political polarization |

Political polarization CI

(Low) |

Political polarization CI

(High) |

|

2000 |

2.087 |

1.658 |

2.415 |

|

2001 |

2.481 |

2.107 |

2.838 |

|

2002 |

2.283 |

1.913 |

2.648 |

|

2003 |

2.08 |

1.677 |

2.43 |

|

2004 |

2.08 |

1.677 |

2.43 |

|

2005 |

1.892 |

1.591 |

2.178 |

|

2006 |

1.892 |

1.591 |

2.178 |

|

2007 |

1.892 |

1.591 |

2.178 |

|

2008 |

1.892 |

1.591 |

2.178 |

|

2009 |

1.892 |

1.591 |

2.178 |

|

2010 |

2.066 |

1.798 |

2.355 |

|

2011 |

2.066 |

1.798 |

2.355 |

|

2012 |

2.138 |

1.867 |

2.432 |

|

2013 |

2.343 |

2.084 |

2.664 |

|

2014 |

3.467 |

3.225 |

3.753 |

|

2015 |

3.581 |

3.394 |

3.882 |

|

2016 |

3.657 |

3.506 |

3.932 |

|

2017 |

3.631 |

3.446 |

3.875 |

|

2018 |

3.642 |

3.485 |

3.914 |

|

2019 |

3.642 |

3.485 |

3.914 |

|

2020 |

3.459 |

3.25 |

3.752 |

|

2021 |

3.467 |

3.206 |

3.727 |

|

2022 |

3.462 |

3.223 |

3.739 |

|

2023 |

3.745 |

3.631 |

3.983 |